Lights of the Past

In all of their types and variations, for centuries have the fishing lights been an indispensable part of the equipment of Dalmatian fishermen. Modern fishing knows many types of fishing lamps: propane lamps for spear fishing, LED lamps for catching squid, big electrical lamps for sardine fishing with purse-seines and so on. The efficiency of all these lights, despite their variety, relies on a basic principle – the fact that in the night time artificial light attracts plankton, a favorite food of many different sea organisms.

This exhibition presents the development of lights used for sardine fishing, by using the lamps from the Fishermen’s Museum in Vrboska. All of these lamps were given to the museum in the past few decades by families from the island of Hvar, mostly from Vrboska.

An illustration of svićarica boat with it’s crew – svićor, šijavac and a third member of fishing crew. Source: J. Basioli, Ribarstvo na Jadranu, 1984.

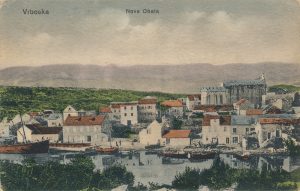

Fire and light have been used in fishing since the antique times, but in our area its use is intensified in the 16th century. It’s not a coincidence that the same century also marks the beggining of an era in which the coastal part of Hvar starts to get more populated, and in which some of today’s settlements, such as Vrboska and Jelsa, start to get the first contours of their contemporary looks. Stable Venetian rule somewhat diminishes medieval threats from the sea, such as various pirates and conquerors, which opens a new opportunity to the agriculture-oriented population from the inland of the island – an opportunity of making permanent settlements near the sea and getting more involved in fishing practices.

A postcard depicting Vrboska, 1921. Institute Olympia, photo: Petar Ruljančić. Source: Beritić family

Earliest confirmation of the statement that fishing was the main cause of settling Vrboska is found in a letter which the pastor of Vrbanj, Vrboska and Svirče sends to the bishop in 1505. He states that a lot of his parishioners have moved to Vrboska, and the main reason was – sardine fishing. Since we know that in some other parts of Dalmatia fishing with light is mentioned already in the 13. century, first in the Statute of Dubrovnik, it is almost certain that these earliest fishing operations in Vrboska also included the use of artificial light – fire.

Giornalle della luminazione, fishing journal from 1889. by Petar Beritić from Vrboska. Fishermen’s Museum in Vrboska.

From this time until the first half of the 20th century, summer sardine fishing with lamps and trate, large shore seines, will be one of the backbones of the island’s economy, and salted sardines, along with wine, will be the most important export product of the island.

SVIĆALO – Pinewood burning light

Two examples of Svićalo, pine-wood burning lamps from the permanent exhibition of the Fishermen’s Museum in Vrboska. (Left – Photo: Andro Damjanić). Fishermen’s Museum in Vrboska

As I ended, the sun began to set,

Night hanging back a little in the East

And hastly they made their tackle ready

And in the torch-rack placed a lighted torch.

We rowed, hugging the shore, at crawling pace,

One rowing while the other held a trident.

Indeed I found it wonderful to watch

How he struck the fish just where it swam!

The above listed excerpt from Petar Hektorović’s Fishing and Fisherman’s Conversations (translation by Edward D. Goy) is the earliest literary mention of the use of fishing lights on the island of Hvar. An idyllic scene in which a nobleman observes fishermen at work alslo brings us a description of the use of the earliest type of lantern – the pine-wood burning torch-rack called svićalo.

Svićalo is a special grid which produced light by burning pinewood. These iron grids were installed on the bow side of the boat, and pinewood logs were burned on them. Although Hektorović’s description illustrates fishing with tridents under the lamp (the following quote mentions two caught lobsters), the main and most frequent use of svićalo was to catch sardines with shore seines with which the catch was pulled ashore. They were used during the summer months during the mrak periods – periods without moonlight.

Fishing spears, two examples from the Fishermen’s Museum in Vrboska.

Carrying trata on shoulders on Riva in Hvar. These big nets were used for sardine fishing with lamps. Source: Prošper Maričić

A larger group of people (10-15) participated in this type of fishing, making up a fishing crew called družina (company) distributed over at least 2 vessels. The net was set on the larger boat called levut, which also carried most of the members of the crew, while the other boat, lojda or svićarica, carried the light which lured the fish towards the shore. The complexity of the work is also reflected in the very clear hierarchy and the distribution of jobs and invested funds in this type of fishing, on which the distribution of catches later depended.

Left: Škandoj, a rock wrapped in net which would be tied to a rope, and with which svićor would be testing the depth and quality of the bottom. Use of this is seen in the illustration presented earlier. Middle: sinjol, a gourd that would show the position of the sak – the middle part of the net. Right: Krok – Fishermen’s belt used for pulling the nets onto the shore. Fishermen’s Museum in Vrboska.

A depiction of the fishing crew. Vinko Foretić, Fishermen in the dawn, 1942. Property of The Museum of Fine Arts in Split. Foto: Robert Matić

Most of the members of the fishing crew were wage earners, mostly farmers who filled their household budgets with night fishing. On the other hand, šijavci, svićori, and paruni were professionals – people with exceptional knowledge and experience in fishing. The success of the entire operation depended highly on their abilities, so they were paid for their services with a large share of the catch. Šijavac was a rower of the boat with the light and the one in charge of logistics – the day before fishing he had the task of chopping pine wood down to size and arranging it in the boat. Svićor was in charge of finding the fish and maintaining the fire, and Parun was the main organizer of the crew in leut, according to whose instructions the net was operated.

PETROLEUM LIGHT

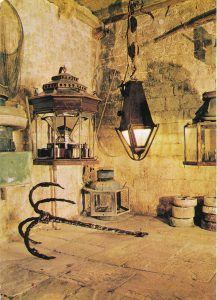

Left: A detail from a postcard, two petroleum lamps from the Fishermen’s Museum in Vrboska. Right: Liquid petroleum lamp made in the workshop of Vicko Kovačević in Hvar in the 1860’s. Fishermen’s Museum in Vrboska.

Many technological innovations made during the 19th century were also introduced in the field of fisheries. In an attempt to ease the pressure on pine forests, but also to simplify and improve the rather exhausting way of lighting with flaming pine, in the 1850s other light sources began to be experimented with – primarily petroleum.

These lamps consisted of petroleum storage tanks with wicks and mirrors that directed the light and regulated its intensity. To solve the problem of excessive logging, the Croatian Government of the Land in Zagreb in 1893 officially introduced and encouraged the usage of these wick lamps, but local fishermen were sceptical towards this invention so they stuck to their old ways and continued to use pinewood.

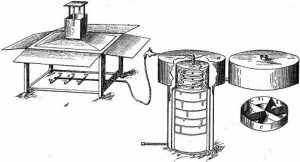

It is interestig that Vicko Kovačević, a tinsmith from Hvar, made one of the more noticeable attempts of improving this system by inventing a lamp which combined eight petroleum lamps placed in a circle with mirrors and small hatches for light focusing. Although this invention was more efficient than the petroleum wick lamps, the light intensity was equal to the light generated from burning pine wood. Further innovations and improvements of this system were abruptly interrupted by the invention of acetylene lamps which due to their efficiency and intensity took precedence in the fishing practices.

ACETYLENE LIGHT

Left and middle: Acetylene lamps with pjati-carburettors, and boca – containers, for carbide. Right: Cetilena – a household lamp powered by carbide. Fishermen’s Museum in Vrboska.

The next generation of night fishing lamps appeared in the late 19th century, during the second industrial revolution. The first night fishing lamp powered by acetylene gas derived from calcium carbide (CaC2), a material locally known as garbura, was invented in Rijeka in 1898.

The first acetylene lamp was invented in 1898 by Ivan Dellaitti from Rijeka. He tested it the same year in Sali on Dugi Otok island with the help of state official, teacher Peter Lorini. On this occasion Lorini wrote:

We will never forget how we felt the moment we lit the first lamp in our hometown when the first ray of acetylene light fell from our hands onto our beautiful sea! Our hearts were beating in our chests, and eyes were glistening from looking at the clear sea illuminated by the brightness of the new light, and from the fullness of our hearts came an exclamation of gratitude: Glory be to Thee, O Lord! A new day has dawned for our poor fisherman; our main fishing has been saved!

A blueprint of acetylene lamp by Ivan Delaitti from 1989. Source: Petar Lorini, Ribanje i ribarske sprave pri istočnim obalama Jadranskoga mora, 1903.

The device consists of two parts: a cylindrical vessel with carburettors in which water reacted with carbide and produced acetylene gas; and a reflector with burners that burned the gas and generated light. In addition to the fact that the light was brighter and better than the light obtained from burning pinewood, this revolutionary invention largely simplified the preparation for lamplight fishing (pod felor) and solved the growing problem of excessive logging of pine trees which were used in fishing. A single night fishing boat (svićarica) with an iron grid (svićalo) would burn 120 m3 of pinewood during one summer fishing season which resulted in complete deforestation of the island at the end of the 19th century.

A postcard from Vrboska depicting a boat with acetylene lamp. Source: Beritić family

According to the records of Captain Luka Dančević, who dealt with this topic in the 70’s when there were still living people who remember the use of svićalo, the last fishermen from Vrboska who fished in this way cut wood on Brač. Precisely because of this, acetylene lamp was a revolutionary invention that solved a number of logistical problems related to sardine fishing, which is why fishermen throughout Dalmatia embraced it very quickly.

However, its disadvantage was that compared to old pine and kerosene lamps, this type of lamp was more dangerous to handle, as any clogging or leakage of flammable and explosive acetylene meant a potential catastrophe. Lamps of this type emitted light of 400-500 candles intensity, and consumed about 264 liters of acetylene per hour, and each kilogram of lime carbide yielded 340 liters of acetylene.

Left: Pjati – carburetors in which acetylene was produced by mixing water and carbide. They were enclosed in cylindrical containers which directed the gas towards the burners. Right: Burners from an acetylene lamp

PETROMAS

A postcard depicting Jelsa and a pressurized petroleum lamp. Traveled in 1965.

The second stage of petroleum light development that will completely replace the acetylene lights begins in the 1920s with the appearance of a new generation of petroleum lamps. So-called pressurized petroleum lamps weren’t using liquid petroleum but petroleum gas that resulted from mixing liquid fuel and pressurised air that was pumped into the lamp with hand pumps. This type of lamp was more efficient, simpler and safer for use than the old liquid petroleum and acetylene lamps, and the intensity of the light was equal to 500-2000 candlepower, depending on the type. In addition to the high light intensity, 1 litre of petroleum could power the light for 3 hours while old liquid petroleum lamps spent 7 litres of fuel per night.

A fishing entrepreneur and inventor, Ivan Skomerža from Crikvenica was the first one to use this lamp on the Adriatic Sea in 1910 but despite many advantages, the lamps weren’t popular until the 1920s mainly because the fishermen were used to acetylene lamps. After a few decades, the news of its benefits in fishing for small pelagic species was spread all over Croatia’s coastal region and petroleum gas lamps soon became the standard equipment for night fishing. In Yugoslavia, in 1939 there were 3465 of these lamps in use.

Interestingly, after the appearance of these petroleum gas lamps the fishermen on the east Adriatic coast had the opposite problem from their ancestors – the light was too strong. In the early 1920s, the fishermen in the neighbouring fishing grounds would frequently come into confrontations in which they used bright lights to attract each other’s catch. That is why the maritime administration of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1926 adopted a regulation that set a limit of the light intensity to 1500 candlepower.

Retina – a small net in which a mixture of fuel and air would be pumped to produce light in pressurized petroleum and gas powered lamps. Fishermen’s Museum in Vrboska.

Pressurized petroleum light made by a German company “Petromax”. Fishermen’s Museum in Vrboska

These types of lamps were mainly imported until the Second World War and the most famous manufacturer on the Dalmatian coast was a german company Petromax whose name, in the “domesticated” variant – petromas – has remained an eponym for all types of these lanterns to this day.

Pressurized petroleum light from an unknown producer. Fishermen’s Museum in Vrboska.

The problems occurred after the war. Many german factories, including Petromax, were destroyed in Allied bombings and the supply of spare parts became a pressing problem for the Dalmatian fishermen. This was the reason why the company Riba-lux was formed in Zagreb in the postwar period. In the beginning, the company specialized in repairs and maintenance, and from 1950 it started manufacturing their lamps. In 1954 the same company replaced the petroleum gas with butane gas which was cheaper by 20%, easier to handle and gave equal results. Butane gas lamps are also being used today for fishing with harpoons under the light (pod sviću).

Left: A detail, plate containing the logo of Riba-lux, a lamp producing company from Zagreb. Right: A lamp made by the Riba-lux company from Zagreb. Fishermen’s Museum in Vrboska.

FISHING LIGHTS TODAY

An early type of an electric fishing lamp, second half of the 20th century. Fishermen’s Museum in Vrboska.

The era of sardine fishing with gajetas, leuts and shore seines ended about 50 years ago with the advent of modern purse seines, but lamps, although in slightly different variants, still remain an indispensable tool for many fishing boats across the Adriatic. With the exception of the aforementioned propane-butane gas lamps that are still in use, fishing lanterns are mostly electric today. Whether it is large lamps for catching blue fish by purse seines, or small LED lamps with different spectra of light for squid fishing, night fishing is still unthinkable without artificial light.

Svićala, acetylene lamps and “petromas” lamps can be interpreted today as developmental stages of modern lamps, but it is important to point out that their economic importance in the historical context was many times greater than today’s fishing lights. These lamps fed countless generations of islanders at a time when fishing, especially sardine fishing, was a key factor in the economy and survival of small island communities. All lamps of the Fishermen’s Museum in Vrboska presented in this exhibition are therefore a direct connection with the fisherman’s past, witnesses of some past times, people, habits and jobs, and authentic mediators of the fishing tradition and heritage of the island of Hvar.

Salting sardines in Hvar in 1938. Source: Prošper Maričić

Some of the items of the Fishermen’s Collection, most of which are fishing lamps, were restored in 2020. The restoration of the entire collection is a priority multi-year program of the Jelsa Municipal Museum, and so far it has been funded by the Municipality of Jelsa and the Ministry of Culture and Media of the Republic of Croatia.